André Staltz

Time Till Open Source Alternative

27 Aug 2022

Open source is coming for your business. It is just a matter of time before there exists a compelling open source alternative to your software. It won’t happen overnight, it will start out as a poor alternative, but slowly growing to become the robust and cheap (in fact, free!) solution that everyone uses.

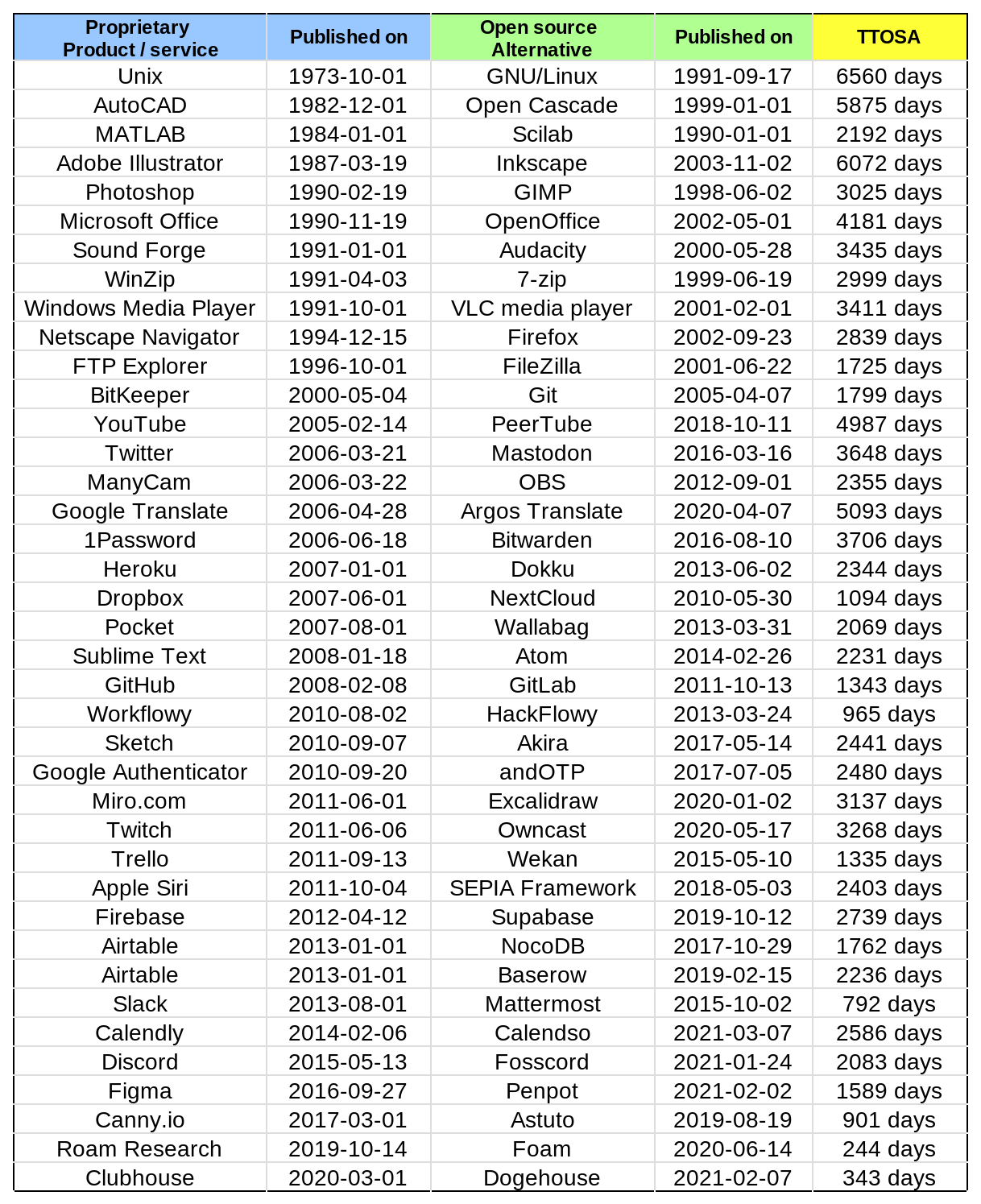

In this blog post, I’ll prove this to you with data. I present a measurement I call “Time Till Open Source Alternative” (TTOSA) which represents how long a proprietary software lasted without a direct open source alternative.

The average TTOSA for the cases I measured is 7 years, and that seems like plenty of time for a business to be profitable with proprietary software, especially given that once the open source alternative hits the market, it still takes years until it can outright displace the proprietary champion. Doesn’t seem like there’s a problem here. However, TTOSA is speeding up, it’s becoming easier and easier to build open source alternatives, and lately we’ve been seeing a lot of them pop up on GitHub. The current world record for quickest TTOSA is 244 days, held by Foam, an alternative to Roam Research. This is a trend, and it means a lot of things for the future of software and the related businesses.

The data

I’ve been occasionally collecting data for this manually, and it’s large enough now to publish. The following table lists proprietary software and corresponding open source alternatives that were directly inspired by the proprietary software. For both, I tried to determine the birth date of the software, which was often either the date the company was founded, or the date of the initial commit. My source for these dates has been Crunchbase, Wikipedia, and git logs on GitHub.

Time Till Open Source Alternative is then defined as the difference between those dates, assuming that the proprietary software always comes first. I identified 39 cases, see the table below, or get the raw CSV here.

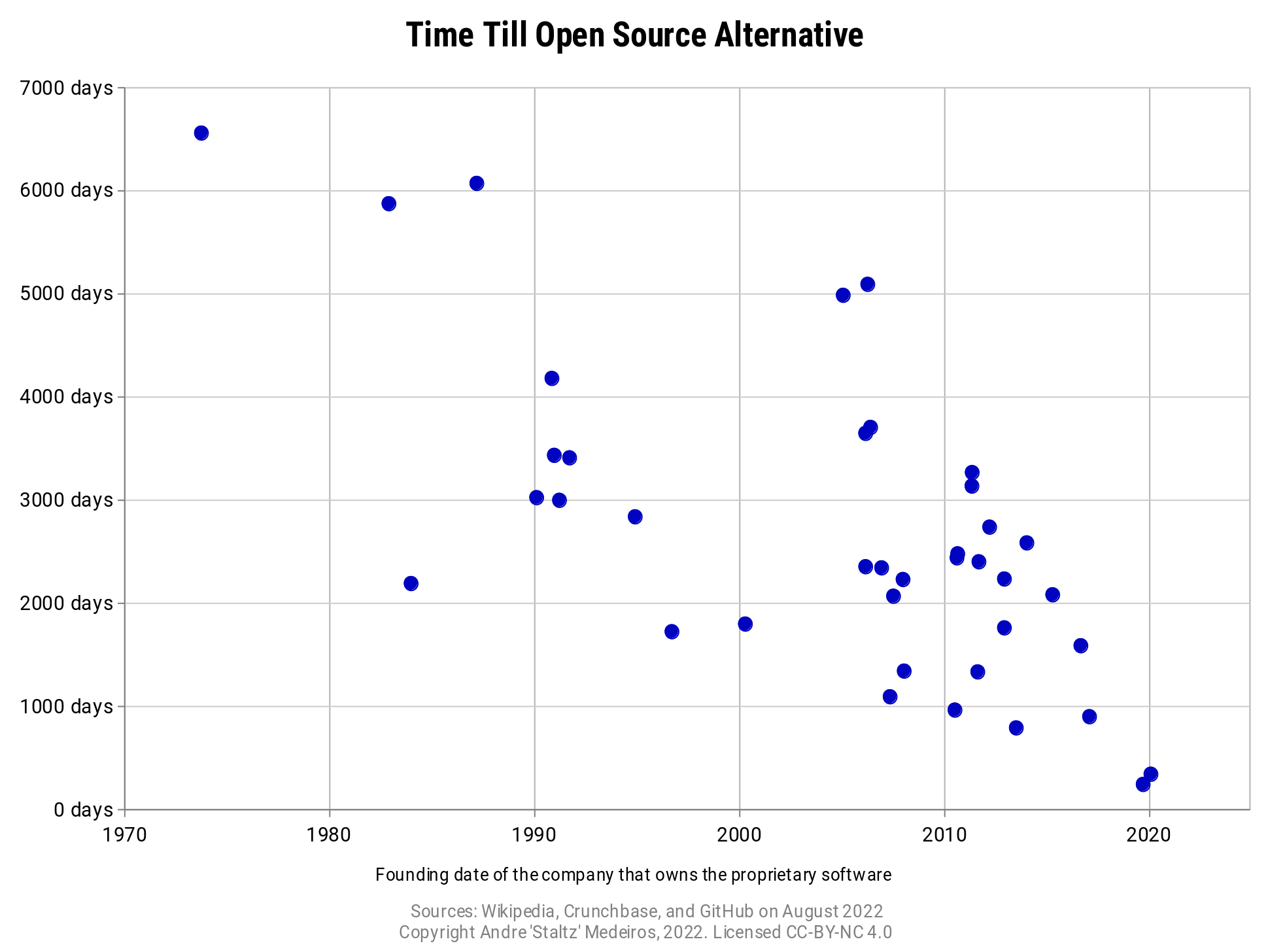

Plotting this data on a chart, where the X-axis is the the date the company was founded, and the Y-axis is the associated TTOSA, we get the following:

Two things become clear with this chart: first, there is an explosion of dots after the mid 2000s, and this probably is correlated with the rise of the Web and subsequently the GitHub era (GitHub was founded in 2008). Second, the trend is downward.

Measurement method

The keen reader may notice that 39 open source alternatives doesn’t seem like a lot. Some popular open source projects may come immediately to mind and not be on that list. For instance, the Apache HTTP Server is not on the list.

That’s because I’m measuring direct alternatives to proprietary software. Apache was not created as a direct replacement for some known proprietary software, even if in practice it could replace proprietary software at the time. Contrast that with GNU/Linux, for instance, where the name “GNU’s Not Unix” makes a direct reference to Unix. Open source alternatives like that will often have the name of their proprietary counterpart mentioned in the README. Those are the types of open source projects I’m covering with this list. If I missed any significant case, please feel free to open a pull request to update the table.

Another important metric is the choice of “birth date” for a project. The day a company is founded, their product barely even exists, and probably the market has no idea about it. So it may seem silly that we’re measuring “time till open source” starting from that date, because the proprietary software has not yet acquired awareness in the market. It may also seem wrong to pick the open source alternative’s initial commit as the day we now have a viable alternative to the proprietary software. At that point, we certainly don’t!

However, we don’t have a good way of determining the day a product has become a viable solution in the market. When exactly did Sublime Text become popular? It’s hard to get an exact date. When exactly did Atom and VSCode rise as popular alternatives to Sublime Text? We don’t know.

So we need an exact date, and the birth date for a project is the best we can get. We then expect that projects like Sublime Text and Atom take the same amount of time to grow from “day one” until “popular”. That’s why we use the difference between birth dates, because it probably approximates difference between market popularity dates well enough.

A couple caveats

Let’s be a bit skeptic about this data for a moment, we can learn a few truths from the details. This list of open source projects has a mix of complex projects, simple projects, popular projects, and just-5k-GitHub-stars projects.

For instance, take BitKeeper (proprietary) versus Git (open source). Anyone who is a developer today knows what Git is, while BitKeeper is just a small anecdote in Git’s history. Contrast that with Apple Siri – known by everyone with an iPhone – versus SEPIA Framework, which has… 70 stars on GitHub.

It is clear that these open source projects are at various stages of maturity and industry leadership, and it’s a long shot to say that SEPIA Framework will disrupt Siri. Just because there exists an open source alternative to something, doesn’t mean that this alternative is yet of high quality. There is often a long journey for these projects before they are ready for mainstream. That’s a whole another aspect to measure.

That said, TTOSA is still a powerful measurement because it tells us it doesn’t take long until you have some kind of barely usable alternative to a proprietary software. If we would measure “Time Till High Quality Open Source Alternative”, we would figure out that… duh… it takes a lot more time. But, maybe we would also find a downward trend in that dataset. And that’s a powerful trend. High quality open source should send a chill down the spine of business dudes, and they already exist: Linux, VLC, Firefox, Git, OBS.

The projects in this list also vary in complexity. It’s much easier to build an open source alternative to a text editor like Workflowy or Roam, than it is to build an open source alternative to YouTube.

Another story to be told is that a lot of these open source alternatives seem to be built by companies, not by open source hackers in their free time, and those companies want to make money. Examples: Excalidraw, GitLab, Bitwarden. The freemium open source business model is basically a way of preventing your company from being disrupted by third-party open source alternatives, because you control the open source to begin with, and you benefit by the community and contributors. This means one thing, though: you admit you don’t make money from software, you make money from something else, be that cloud hosting, support, corporate-specific features, or something else.

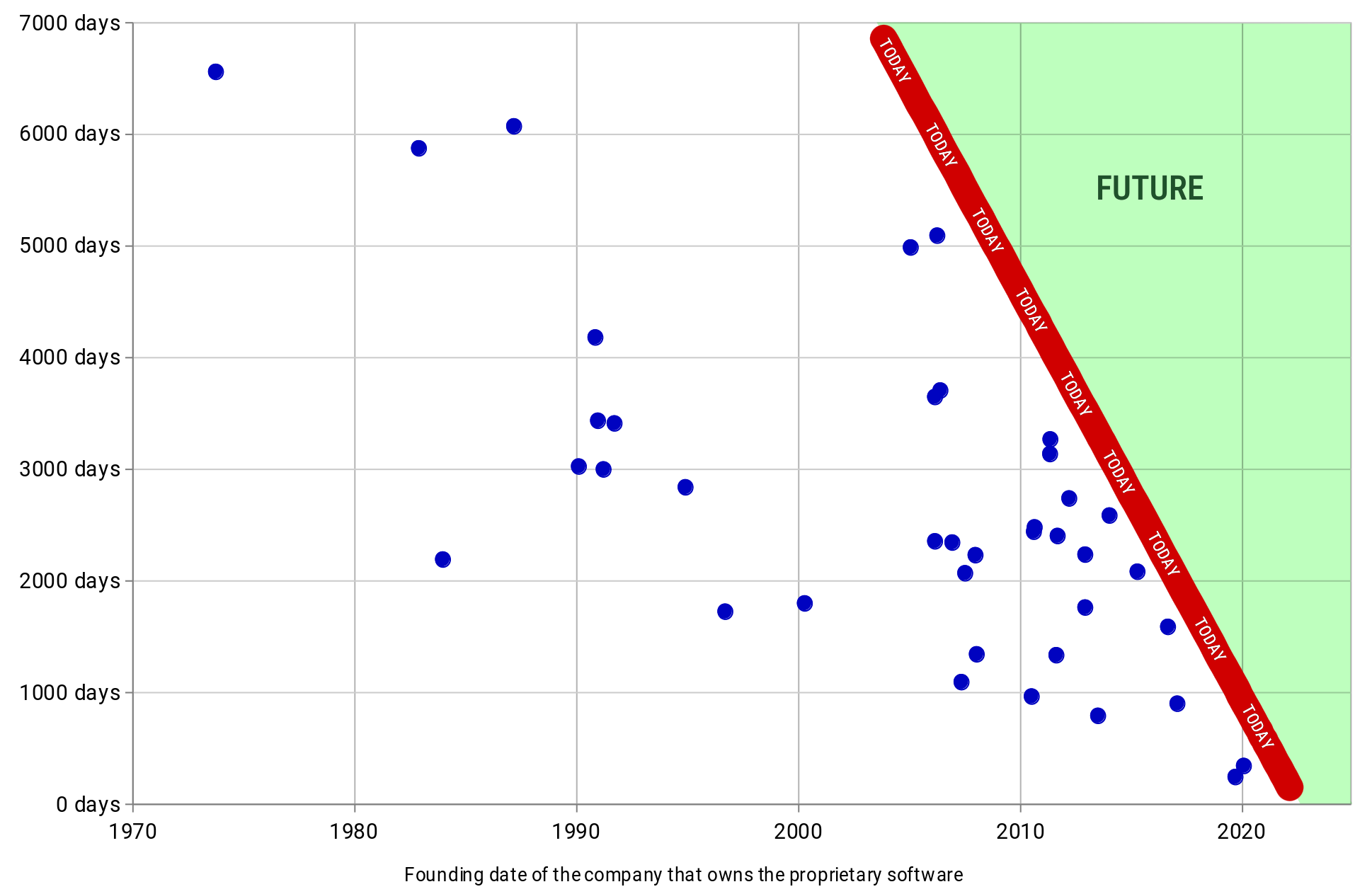

Finally, a blind spot in this dataset is the green triangle in the chart below:

It means that maybe soon in the year 2023 there will be a lot of open source alternatives discovered that have a TTOSA number as high as (say) 5000, thus landing the green area above. This would mean our “downward trend” is incorrect, because we haven’t waited long enough to see the full picture.

That is a theoretical possibility, and the green triangle will always exist in this chart, no matter how far in the future we go. A counterpoint to this blind spot is that the world record for lowest TTOSA is being broken, decade after decade. In the 80s it was 2192 days, in the 90s it was 1725 days, in the 2000s it was 1094, in the 2010s it was 244.

The endgame?

All software will be open source, and no one will make money with software.

That’s a pretty tough claim to accept, so let’s digest it in parts. Is all software becoming open source? You will always be able to write software and keep it secret, so that’s already a refutation. Not all software will necessary be open source. That’s not my point.

My point is that all software in the market will be open source, and it’s caused by two trends. (1) Software is becoming easier to create and easier to share its source code. The rise of high-level and/or interpreted languages made the creation of software easy, and something you can do in a few weekends if you want to. The rise of GitHub means you can upload your project with three words and 10 seconds: gh repo create. And this is a feedback loop: libraries made open source end up being used to increase productivity of more and more programmers, who in turn publish more open source code.

(2) Closed software dies when resources run out, but open source software only dies when public interest runs out. There are several examples I could mention of brilliant proprietary software that existed for a brief duration of time, simply because the startup that birthed it went bankrupt, or the tech giant discontinued the product because of resource allocation. I believe you can come up with your own recollections of these.

On the other hand, open source is born public, and receives care from fellow contributors in proportion to the amount of attention and interest the project gets. I’m not saying that open source projects never die, some definitely do. I’m saying that popular open source projects never die, because once they are popular enough, there is a sufficient amount of contributors to keep it alive. As a vivid example of this, my friend and ex-coworker Jani Eväkallio built Foam in 2 months and then unfortunately burned out. He never touched Foam ever again. However, by that time, the project gathered enough popular interest, and there are regular contributors who keep the project alive and relevant, updating it every month, for the past 2 years.

Over time, this means that the open source ecosystem has a unique leverage over the startup ecosystem: startups have runways which prevent the indefinite growth of their product, unless they hit the right combination of luck and customer satisfaction. But popular open source is unconstrained, it only gets better over time. And we’ve come a long way. Blender used to be cringe for 3D modelling, nowadays Blender is punch-in-the-face awesome, and it will get even better.

Finally, to address the “no one will make money with software” claim. Open source software hardly makes any money, and will make even less money in the future. I explored this point in depth in a previous blog post titled Software below the poverty line. The effect this has on the market is that it reduces the price point of software, no matter if it’s open or closed. If your closed software demands $1000 from my pocket but I can make do with a free and open source alternative, I will choose the open one.

At a macroscopic scale, this forces closed software companies to reduce their pricing to better match what you can get in the market. Many of these companies are now providing their software at price zero, and they monetize in other ways. B2B companies (like GitLab) just make their software open source and quit trying to compete in the software-for-sale market, monetizing on support, hosting, and other means instead. B2C companies like social media platforms monetize on attention, via ads. They could open source their software, but it makes little sense, because it’s so closely tied to their data center infrastructure. The point to be made here is that those platforms monetize their databases, not their software. In fact, their software is largely oriented towards taking good care of that valuable, humongous and sensitive database. Software itself really doesn’t have a future in making money.

In the future – and maybe it’ll take a couple more decades – all software will be open source, and no one will make money with software. And I think that’s a good thing.

Copyright (C) 2022 Andre 'Staltz' Medeiros, licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC 4.0, translations to other languages allowed.