André Staltz

The Cybe

28 Oct 2018

Some months ago Teemu Paivinen and I met for coffee in the center of Helsinki. We discussed all things peer-to-peer and global issues like economics and the internet. Deep into the conversation, as Teemu gazed outside the window trying to grasp for words, he shared that he felt there was something about the exponential scale of the internet that makes it more important than we realize. Neither of us were able to put into words what that is, but I knew what he was talking about. Yet, it bothered me that we couldn’t articulate the idea, and I kept thinking about it weeks later. In this article Teemu and I try to articulate that idea, give it a name and create the beginnings of a framework for thinking about it.

People often talk about “cyberspace” and other cyber-related words. Cyber- is a prefix that works as an adjective, adding internet connotations to the noun that follows. It points to a known concept, but we rarely talk about what that concept is. What’s needed is a noun, not an adjective.

Graphs

Information science has a foundational mathematical tool, Graph theory. In informal language, a graph is a bunch of dots connected by a bunch of lines, and can be applied to describe cities and highways, computer systems, words and their relationships, etc. The internet is a graph, where nodes are computers and edges are the connections between them. The internet also contains also other virtual graphs, like the social graph, where nodes are user accounts and edges are follow relationships.

An edge only exists to link two nodes together. Without nodes, there are no edges. So it would logically follow that the nodes are the primary concept in graphs. For years we have fixated our attention on the nodes that make up the internet. We have counted the number of websites, users and views as the core metrics by which we evaluate the utility of the internet.

Edges

But we may be missing something important. In highly connected graphs, the number of edges is (at most) quadratically larger than the number of nodes. This means that a cyberspace with just a humble amount of two thousand people can display more than a million interpersonal connections. A cyberspace with two billion users (e.g. Facebook) could have many trillions of connections. One Imagine this: if you spent one second looking at each interpersonal connection on Facebook, ten thousand years would not be nearly long enough to see them all.

We can only estimate the amount of edges on the internet. Doing a simple web search, we can’t discover the total number of hyperlinks on all websites, we can’t lookup the number of follow relationships on Twitter. We don’t seem to be publicly tracking these numbers, but they are fundamental in describing the value of a cyberspace. A collection of a thousand isolated individuals is nowhere near as valuable as a system with a thousand highly-interconnected persons.

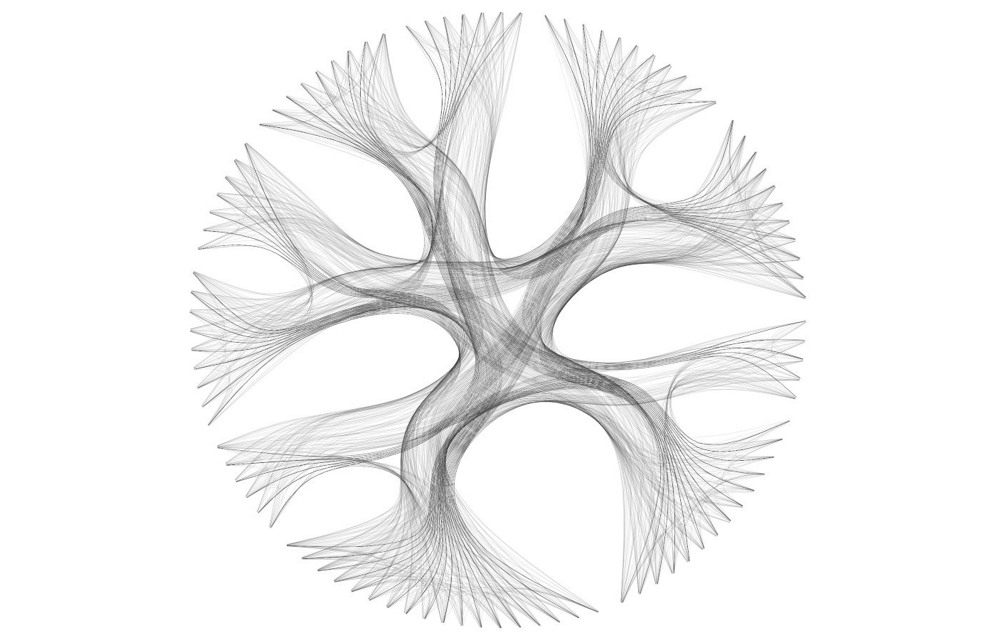

At scale, the edges gain a central role and overshadow the contribution of any individual node. This is what we call the Cybe: the set of edges in any large and dense graph of agents, where edge count is in the trillions or quadrillions. The Cybe is the name given to edges when they collectively become an entity in itself, with properties that resemble an intelligent agent.

Although the internet is at least a couple decades old, the Cybe is new, due to two recent trends: increase in the number of edges, and improvement of edge quality. The number of internet users only recently reached numbers large enough to make it possible that there are trillions or quadrillions of edges. These edges are also more busy and more efficient than decades ago, due to the increase of instant messaging and social media. With smartphones, people use computers daily and potentially even hourly, much different to the sporadic internet usage in the 1990s. One could say we are now witnessing the real internet, while before it was just the proto-internet.

Comparison with the Brain

The Cybe is approaching qualities reminiscent of the human brain, which contains a couple billions of neurons and half a quadrillion synapses, and neurons are collectively – not individually – responsible for intelligence and behavior. The Cybe is what defines large-scale social dynamics on the internet, where people care less about the individuals involved than they care about congregating within the Cybe. Like the Brain, certain regions of the Cybe are sensory, comprising of professional journalists, citizen journalists, and the media. Other parts are merely excitable “neurotransmitters” that relay content from one part to another. The Cybe can also display collective intelligence and produce content. Wikipedia is a prime example of that, where humans become collectively knowledgeable.

Unlike the brain, however, the Cybe is not made of nodes of the same nature. The Cybe contains human nodes, but also diverse kinds of non-human nodes: impersonating bots, non-impersonating bots, platform software that regulates publishing and browsing, news feed algorithms, ads and ad networks, crawlers, miners, etc. The Cybe is less like a synergetic superorganism, and more like a Holobiont, a term in biology to describe an ecological unit composed of different species.

While the brain seeks for homeostasis, a state of steady internal conditions to support survival of the organism, the Cybe is chaotic and its parts may be in competition and have dissonant goals. An organism and its surrounding environment are separate things, but the Cybe is simultaneously an environment, a market, and a collective intelligence. It is an inharmonious intelligent agent with diverse purposes, sometimes honourable, sometimes inhumane.

Even though it lacks balance like biological homeostasis, the Cybe already has cyberhormones. The brain and the physiology of an organism make use of hormones to regulate behavior and internal coordination. Cyberhormones are game theoretic mechanisms of incentive in cyberspace. They are fundamental to explain certain kinds of behavior in the Cybe, like viral propagation of content or cryptocurrency mining. Biology has had many millennia to evolve hormones in species like humans, but the Cybe is young and not self-regulating very well.

Control

Being powerful, large, not entirely human, fast, and chaotic, the Cybe is being perceived as a threat to various forms of human power. There is increasing interest in mechanisms to control the Cybe. We can identify three types of control vectors: regulation on centralization, artificial intelligence, and cyberhormones.

Many governments are viewing cybernetic power as a threat to politics. To reduce the extent of cybernetic power, governments believe in law and regulation. They make the assumption that cyberspace is controllable simply because most of it is proprietary and falls under the responsibility of a few tech platform companies.

Centralized platforms literally host the Cybe, so governments assume that the host can control cyberbehavior. Regulating the inputs (consumption) and outputs (production) of information flow would be enough to curb the power of the swarm. What governments miss, however, is that scale makes a difference in that kind of control. In a small cyberspace of a few million nodes, this kind of regulation on the I/O boundaries can be effectively accomplished, but not in a massive cyberspace with quadrillions of edges. For instance, centralized app stores have a few million apps each, and it is feasible to hire a few thousand employees to regulate app submission at the I/O boundary and have sub-hour efficiency. At a larger scale, the number of employees required for that kind of task might exceed the human population.

This is why tech platform companies are consistently proposing the use of artificial intelligence to automate control in cyberspace: swarms of computers with super-human and focused skills in controlling cybernetic behavior in the I/O boundary. Input regulation would mean AI-driven algorithms that filter content for consumption, and output regulation would mean AI-driven detection of forbidden content. These strategies are currently being pursued by tech platform companies.

However, artificial intelligence at the I/O boundary might not be enough to control cybernetic behavior, because I/O happens on the node level, while cybernetic behavior is all about the edges. For instance, it may be possible that the Cybe utilizes viral propagation of content that passes the I/O validation by the AI, but collectively and as a swarm causes undesired behaviors. In other words, information may not be in isolation considered harmful, but its propagation within a certain context may be considered harmful. Winnie the Pooh depictions of Chinese president Xi Jinping is a example of that behavior, and while it can still be controlled on the I/O boundary, this usually happens much after it was observed as a collective behavior.

Regulation and AI can sometimes work to control the Cybe, but they are not cyber-native solutions. Cyberhormones, such as game theoretic incentives, are. Meme engineering, social engineering, proof-of-work, proof-of-replication, are examples of such. Unlike regulation and AI, which aim to selectively reduce the cybernetic power, cyberhormones aim to steer cybernetic behavior, while often also increasing the overall size of the Cybe.

It may be that we are witnessing the formation of a new kind of society. The Cybe is a new form of human-machine collectivism on a global scale. It is not clear whether we can exit it or control it, but we can study its behavior, study cyberhormone engineering, and attempt to make it a better place for humans to congregate in.

Copyright (C) 2018 Andre 'Staltz' Medeiros, licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC 4.0, translations to other languages allowed.