André Staltz

A plan to rescue the Web from the Internet

18 Dec 2017

My previous article, The Web began dying in 2014, here’s how, raised much more awareness than I thought it would. Many people found it to be an insightful analysis of the Web under the control of tech giants, but the article ended without providing anything positive to hold on to.

I actually have hope for the Web. There are legimately viable ways of preserving freedom on the Web while taking the platform forward and keeping it competitive against proprietary alternatives from tech giants. But it can only happen if the Web takes a courageous step towards its next level. If it stays in its current form, the Web has little chance of being relevant while America’s FCC kills Net Neutrality rules, the W3C favors DRM, and tech giants build their Web-less vision of the future.

The community of peer-to-peer technologists has brought to the world several revolutionary technologies: USENET, Napster, BitTorrent, Kazaa, Skype, Bitcoin, Ethereum, and actually even the Web itself. Once again, we can turn to this community to seek digital solutions that defend freedom. Many months ago I quit my job in order to join a group of peer-to-peer programmers and help build technology that can rescue our digital freedoms. I want to share with you our plan, which in short is:

Build the mobile mesh Web that works with or without Internet access, to reach 4 billion people currently offline

To explain this plan, we need to realize that the Web can be independent from the Internet. The core weaknesses of the Internet have to be recognized, and how exactly they were exploited by middlemen businesses. The problem we are solving is both social and technical, so the solution must be a harmony of these two. Finally, all the tools and opportunities we need to supersede them are already in our hands: smartphones, peer-to-peer protocols, and mesh networks.

The rise of closed cyberspaces

The Web is an open cyberspace, a digital context where society can happen, where no single organization, company, or government has the final word on what is allowed or forbidden. It is also an access point to other cyberspaces. Every time you “sign in” with an account on a website, you are entering a closed cyberspace. These cyberspaces are hosted by servers owned by the company or organization behind that website.

Most closed cyberspaces don’t threaten the Web’s role as a public space. A school’s intranet is a closed cyberspace, and so is a private discussion forum or a company’s internal discussion platform. Most people will understand how it is necessary for those cyberspaces to be closed and controlled.

The real threat comes with giant closed cyberspaces that disguise themselves as public spaces. Facebook, for instance. Many of its users think of it as a neutral public space where society comes together, and in fact Facebook often efficiently carries out that role. It is, nevertheless, closed and controlled. It started as one of those justifiably closed cyberspaces: it was a private community of Harvard students. With its explosive growth, though, it had to quickly evolve to encompass all types of social structures.

While Facebook was growing on the Web, Apple launched the iPhone in 2007, and the world was revolutionized by smartphones after that. Zuckerberg saw the mobile megatrend before many others did, and as early as 2009 there was a Facebook mobile app with explosive growth. Facebook began re-imagining itself as a platform independent from the Web.

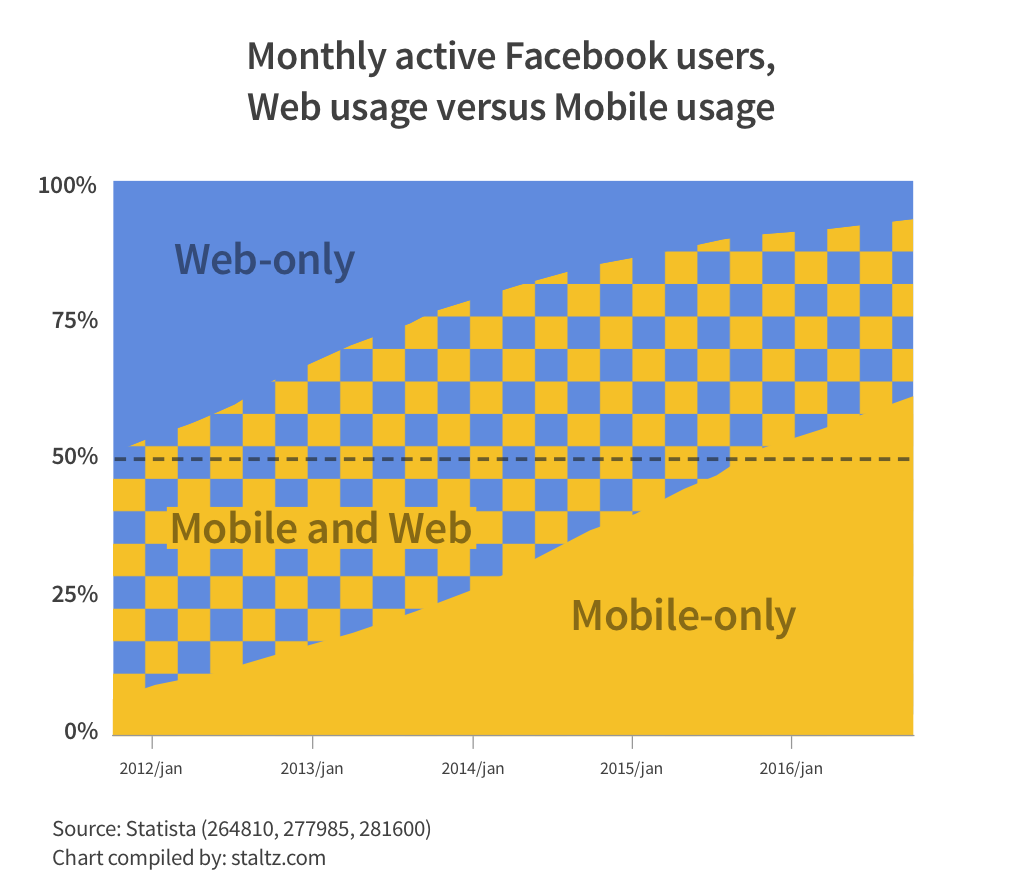

Fast forward to December 2016, and 94% of all Facebook monthly active users access the blue closed cyberspace routinely through mobile apps (divide mobile MAU by MAU), while 62% access it only from mobile (divide mobile-only MAU by MAU). As a result, 84% of FB’s revenue comes from mobile advertising. As an extrapolation of this data, their mobile-only users likely comprise today (December 2017) between 70% – 79% of all their users.

Those are large enough numbers to admit that the open Web is already rather irrelevant to Zuckerberg’s products. By now, Facebook, Messenger, Instagram, and WhatsApp are arguably non-Web closed cyberspaces of comparable scale to the Web (users of FB products are roughly 2/3 of all Internet users). Facebook even has its own concept of cyberwarfare.

It competes with the Web in many use cases that people want from a public cyberspace: sharing notes and images, engaging with communities, doing business, marketing services and products, and organizing events. Similarly, this argument can also be made for YouTube. In fact, any closed cyberspace that grows too much could become a threat to the open Web.

Which brings me to the question: is it fundamentally inevitable that a closed cyberspace will use the open cyberspace to eventually outgrow it? I would answer: no. The Web only got to this current situation because of fundamental flaws in the Internet’s architecture which rigged the system. Closed cyberspaces thrive because they have artificially imposed incentives to thrive.

Technical flaws that supported middlemen businesses

The Internet that supports the Web (as well as other applications such as email, Skype, WhatsApp, online mobile apps) is a technical marvel, but it shares similarities with some archaic systems.

The way data travels through the Internet is quite similar to how the postal system works. Each recipient needs a unique address. On the Internet, these are the so-called “IP addresses”, which are simply numbers given to each computer. A computer may be assigned the number 198.153.192.40, where the first part 198 refers to a specific region in the USA, and the other numbers help specify which particular computer in that region is the recipient.

Here’s the problem with IP addresses: there aren’t enough of them. When the Internet was being planned, it was initially a system of military and university networks. They did not account for the massive popular adoption of the Internet that made it mainstream in business, commerce, and for inter-personal communication. Imagine if there could only be a limited number of mailboxes in the postal system – that is virtually what occured to the Internet.

There was a quick solution to this, though: a mechanism called Network Address Translation (NAT). Jargon aside, it’s a simple idea: one computer gets a real IP address and acts as an intermediate for other computers which do not have real IP addresses. Imagine that your neighborhood would share a single mailbox, then one person would be responsible for sorting and forwarding each received mail to the correct final destination. That is what NAT accomplishes for Internet addresses, and it is commonly deployed on local routers, such as the box you might have installed in your home or office. The advent of NAT routers also allowed for that intermediate computer to become a guardian and protect other computers from some dangers of the open Internet.

It also meant that some computers were first-class citizens on the Internet, while other computers were subordinates. In addition, the scarcity of IP addresses caused them to be considered valuable assets, and so it became a business opportunity. IP addresses are being sold so that some computers can become first-class citizens on the Internet.

It seems easy to solve this problem, though: just provide more IP addresses, since they are after all just artificial resources. That is what IP version 6 is all about, and its purpose is to make sure there would always be enough addresses for everyone (the limit is more than a trillion trillions). However, IPv6 was declared ready for use in 1998 – two decades ago – but its adoption among organizations around the world is still just catching up, because it demands teaching every Internet-connected machine to understand and utilize the new types of addresses.

There isn’t enough economic incentives for IPv6, though, since the information industry has made its nest in massive systems that assume IPv4 plus NAT. Companies that sell IPv4 addresses see little benefit in adopting IPv6 and companies that depend on IPv4 + NAT systems prefer to avoid the risks associated with disturbing the infrastructures that power their always-online businesses. Even if all the computers started using IPv6, too many programs were built with NAT in mind, which could reveal many security vulnerabilities when exposed to a world without NAT. In other words, the Internet economy simply isn’t ready for a scenario where IPv6 is used everywhere and NAT is abandoned. We are stuck with what we have.

As a consequence, the Internet has allowed intermediate computers to rule. These are like parasites that have grown too large to remove without killing the host. The technical flaw that favored intermediate computers prefigured a world where middlemen business models thrive. Google and Facebook connect consumers with advertisement publishers, and charge fees for each ad. Amazon is a middleman business as well: it connects retailers with consumers, and takes a cut on transactions. Many popular ‘sharing economy’ startups and services are also middlemen: Airbnb, Uber, Kickstarter, Patreon, and many others.

It is hard to imagine how things could be different, yet the incentives for these businesses to exist were artificially erected. It is not fundamentally necessary to have any intermediate company profiting whenever a person reads news from their friends, rents an apartment from a stranger, or orders a ride from a driver. This is why it is important to analyze technical systems from an economical and societal perspective: because early design decisions foreshadow certain social orders.

We can – and urgently must – provide alternative ways of digitally supporting popular use cases for Web services. It is possible to escape middlemen businesses by decreasing reliance on the infrastructure that plugs their systems together: wires.

The Internet, on a leash

The physical foundation of the Internet is a global network of thick bundles of privately-owned fiber optic undersea cables spanning oceans to connect all the continents together. Undersea communication cables exist since the 1850s.

(Source: Reuters/Landov)

These cables follow a hierarchical layout: continents are connected to other continents, countries connected to countries, and within those countries, different companies (Internet Service Providers, ISPs) have to agree with their local government in order to plug into that network of cables. This well organized hierarchy is the only way the wired Internet can be feasible. Otherwise, a grassroots wired internet would be a true mess of cables. Countries and organizations also manage the distribution of IP addresses.

Although the Internet is praised as the technology that ushered us into a new era, the information age, it is just a fancy way of transfering data from computer A to computer B. It is highly efficient in transferring data globally at almost instantenous speeds, but it is nevertheless much like a USB cable that connects your computer to an external hard drive. In fact, transfer speeds are almost always better through USB cables than through the Internet. The real benefit of the Internet is instant globalization through the fact that it makes all computers in the world seem like they are in the same room.

The global real-time economy enabled by the wirenet is a historical achievement with permanent implications to humanity. That said, often we engage with apps that have no need for global connectivity. For instance, staying in contact with friends in the same city – a naive but likely the most popular use case for technology – requires no connections to countries on the other side of the planet. Yet we overutilize the global tangle of inter-connected cables to run proprietary and foreign (often American) apps which deliver messages that travel around the world just to reach a colleague nearby. This has opened our lives and our nations to digital colonialism from surveillance capitalism corporations (pick your favorite Silicon Valley company) married to three-letter intelligence agencies.

What could be the alternative? So much of our digital lives depend on technologies that are out of our reach, physically, legally, and economically. Gladly, technology itself has recently provided the first building blocks that can be put together to create a new cyberspace.

Untapped opportunities

Technological innovation is quick to introduce amazing things such as smartphones, 4G connectivity, cryptocurrencies, and digital social networks. None of these existed when the Internet was being planned. Yet all of them rely on the very old idea (from the 19th century) of telecom companies, not as a fundamental requirement, but due to lack of alternatives.

As a thought experiment, how would the Next Internet look like if it were reinvented using all the accumulated knowledge from the last 3 decades of global cyberspaces? There are three promising things that can enable a reinvented Internet:

- The people-centered Web

- Mobile mesh networks

- 4 billion people

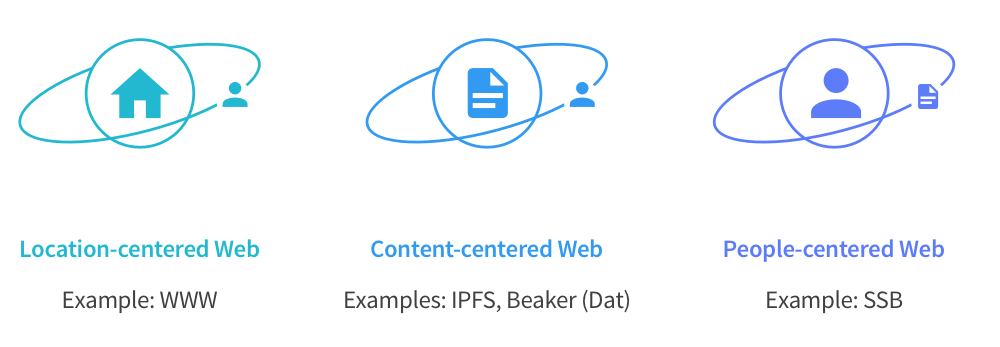

The Web is classically a location-centered cyberspace. When you access the Web, you visit locations (URLs, like wikipedia.org) that contain content. You often don’t see the people who created that content, but they are implicitly assumed to be there. The problem with location-centered content – prefigured by the way HTTP was designed – is that it’s not easy to archive for posterity. An image hosted through some link may be there today, but maybe not tomorrow.

Novel peer-to-peer protocols such as IPFS and Dat help replace HTTP and make the Web a content-centered cyberspace. This way the link to an image can be something like QaPdNnDWRLF1b – a so-called hash of the image, summarizing it – instead of mywebsite.com/pic.jpeg so that even if mywebsite.com servers are removed, you can still get the image by fetching it from any computer that has stored QaPdNnDWRLF1b. If you don’t like the unreadable code, you can just use a link shortener like bit.ly to create a shortcut to the unreadable code. This way, even if your bit.ly short link disappears, the content can still be recovered from the crowd of online computers.

Browsers can be made to work like that, and although it’s a small tweak to how the Web works, it has massive effects on social structures in cyberspace. The Beaker Browser is the best demonstration of that, which you can easily install and start using today. It allows your browser to directly share content with other people’s Beaker installations, without intermediate servers (like YouTube servers, Medium, blogs, etc).

These above mentioned technologies fix the Web by making it truly content-centered instead of location-centered. That said, the Web is good at putting content on stage, while keeping content authors in the backstage. While there are many use cases where it’s desirable to de-emphasize people, such as anonymous reports, crowd-sourced encyclopedias, and cat videos, in the recent years we have discovered a game-changing way of structuring cyberspaces: the Social Web, where content orbits the author like planets orbit a star.

It makes sense for a cyberspace, a digital context for people to engage with each other, to be people-centered. Websites in the social realm took a daring approach of making You a location: the URL twitter.com/andrestaltz means that this content is a person. In fact, one of the earliest large social networks was named Myspace, emphasizing the location and its association with a person. We all have experienced how revolutionary this concept has been, and how it has pervasively reached to many corners of the Web: you can sign in with a Facebook account or insert blog comments using your Facebook profile.

Now that we have experience with some of the intricacies of the social Web, we can reinvent it to put people first without intermediate companies. The peer-to-peer protocol Secure Scuttlebutt (SSB) does that, designed with diversity-first principles that prefigure (hopefully) social structures with freedom, subjectivity, and political structures that can prevent capitalistic monopolies. SSB was envisioned and created by a nomad programmer who had unreliable Internet connection and wanted to enable social networks for off-grid lifestyles. A growing community of pioneers and programmers are using SSB on a daily basis as their main social network. I really hope you click through all those links and explore SSB in more depth.

The mix of off-grid lifestyles with digital social networks is unusual, because we tend to associate technology with dependency on the Grid for energy and Internet connectivity. However, to create an alternative to the Grid, we need to look for technologies that provide energy and connectivity without the Grid. Solar panels provide the former and are a staple of the off-grid sustainability movement known as Solarpunks. To provide the latter, we can use wireless technologies.

Cables gave birth to the information age, but wireless gave us wings to go untethered. And today, digital society gets together through smartphones more than it does through desktop computers. While smartphones enable us to easily share files directly to other devices – without intermediates – using Bluetooth or Apple’s AirDrop, we don’t transfer data through that as compulsively as we do through cables. Wireless technology exists today as a mere extension of the wired world, but it could be so much more than that. It could be, in fact, the opposite: wires as a mere extension of the wireless world.

You probably haven’t heard of mobile ad-hoc networks (MANETs), also known as meshes. One of the reasons for their lack of popularity is that meshes would threaten the business of telecom operators, so there is little incentive from the establishment to develop and deliver mobile ad-hoc networks to you. A MANET is like AirDrop, but automatically and seamlessly connects to devices around you and delivers data in multiple hops between those devices. Even if Bluetooth connections can only reach a few meters, after multiple jumps, you can connect to devices a few kilometers away. Information literally spreads through the air to a mesh of devices in a region. It is propelled even more by the fact that mobile devices are moving around, doing half of the work of transporting data.

On the other hand, the primary reason why MANETs are underappreciated is that they do not yet provide data transfer speeds comparable to those in the wirenet. A MANET upholds principles like freedom from fixed intermediate organizations, but it is simply too slow for transfer-intensive use cases like streaming video or instant messaging. Their adoption would feel like a step backwards to the early days of the Web when speeds were measured in a few Kilobits per second, not the usual Megabits per second you are used to in developed countries.

Mesh networks are nevertheless still promising, for two facts. First, the technology is evolving, with Apple MultipeerConnectivity and Bluetooth Mesh as a few cutting-edge examples. Novel protocols are being developed that envision IPv6 without ISPs, ideal for meshes. Second, because many developing countries do not yet have Internet access. This accounts for 4 billion people, out of the total 7.6 billion, with currently zero bits per second of transfer speeds. Even if it seems like the Internet encompasses the whole world, it still barely reaches 45% of the planet. Some may have Internet connectivity, but it’s intermittent or not consistently speedy. For people with intermittent or unexistent connectivity, ISP-free mesh networks with moderate but consistent speeds become quite attractive.

Image: Internet users in 2015 as a percentage of a country’s population by Jeff Ogden (W163)

Facebook and Google are desperate for getting an early grip of those 4 billion people, e.g. through Internet.org and Project Loon. However, because their middlemen businesses are tethered to the Internet, all of these projects require the old hierarchical structures of ISPs and cables. Their businesses and modus operandi are inherently infrastructure-heavy. The difficulties are several: balloons cannot reliably cover all the regions, local ISPs or local governments may be corrupt, and any other wired infrastructure project takes years or decades.

The exciting part is that we can actually beat the tech giants at this game by simply giving local and regional connectivity to people in developing countries. With mobile apps that are built mesh-first, the smartphones would make up self-organizing self-healing MANETs. Frankly, this is quite easy to do, if we are willing to gift mobile devices without expecting anything back, unlike tech giants. It won’t be an easy fight, though, Facebook is working hard to build a compromise that still gives them the middleman upper hand. Zuckerberg’s 10-year roadmap puts connectivity projects in the long-term spectrum (5–10 years). That’s basically our deadline, we need to get grassroots meshes in Africa before that.

The mobile apps for meshes would have to be best suited for the particular limitations of (current) MANET technologies. Video streaming and instant messaging are not the first options, but lightweight websites in content-addressed style (like in the Beaker Browser with Dat) and text-first social news feeds are applications that can be realistically delivered in the short term. Such apps don’t even require constant connection to other devices in the mesh. For text-based social news feeds, it suffices to occasionally sync the latest news with other devices whenever they are in range.

Even the mobile apps themselves can be deployed through MANETs, and I have already developed an “app store” mobile app that fits that use case, called Dat Installer. My main project at the moment is to build a mesh-friendly social network mobile app running on SSB. It is important to highlight that while these apps are built for meshes, they know how to ‘surf’ the Internet and utilize it as a fallback.

When talking about decentralized peer-to-peer protocols in 2017, it is imperative to mention blockchains and cryptocurrencies. These are great innovations and directly tackle intermediate organizations (mostly banks) as a problem, much like IPFS, Dat, and SSB. On the other hand, most blockchain protocols were designed with high Internet speeds, powerful hardware, and global connectivity in mind. What most of these innovations share in common is the accomplishment of a distributed global database where no single actor is to be trusted above the others. There are legitimately useful use cases of this, such as decentralized Web domain registration. On the other hand, requiring global consensus, high Internet speeds, and powerful hardware makes it difficult to utilize blochchains for mesh networks in developing countries. Alternative not-quite-blockchain experiments like IOTA might change this, though.

The plan

While growing local mesh networks for-charity in developing countries is the proposed strategy, how is it connected to a plan for countering the tech oligarchy in developed countries? In Internet-less regions there is potential for scaling quickly, and through that we can spawn a new industry around peer-to-peer wireless mesh networks. If this industry grows, it can also support meshes in the developed world. Scaling fast is important to make meshes more than just niche projects by a few enthusiasts, but instead become a thriving ecosystem. The mega-projects listed below are a plan to rescue the Web from the Internet:

In the next year or two:

- Developers improve peer-to-peer protocols that support the content-centered Web (IPFS, Dat) and the people-centered Web (SSB)

- Developers and hardware manufacturers write open protocols for mesh networking (comparable to MultipeerConnectivity, CJDNS, Open Garden)

- Developers bring peer-to-peer protocols to smartphones and build mobile apps that use those

- Web enthusiasts and archivers help migrate content from the old Web to the new protocols

- Hardware startups compete in the market for regional mesh networks (e.g. goTenna, Beartooth, and others)

In two years or more:

- Smartphone manufacturers sell mesh-first mobile devices for the developing world

- Developers work with regional communities to localize mesh mobile apps (note the possibility of forking open source projects and customizing them to different cultures)

- Charitable organizations or companies offer mesh-first smartphones for free (or subsidized and cheap) to people in developing nations

- Mesh-based cyberspaces start to thrive in some countries

- Similar mesh cyberspaces in the developed world also gain relevance, specially in countries with unfair ISPs

In six years or more:

- Ecosystem of wireless mesh networks expands from regional “airnets” to national airnets

- National airnets are weaved together through a global mesh of satellites (much like Blockstream)

- Make the global airnet competitive with the wirenet

As a result of having competition between the two, we can hope to fix the overutilization of the wirenet and the underutilization of airnets, bringing balance to the wire-versus-air dichotomy, providing choice in how data should travel in each case.

Choice is freedom.

Copyright (C) 2017 Andre 'Staltz' Medeiros, licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC 4.0, translations to other languages allowed.